The Stubbornness of Participation

Atlanta has a pollen issue. While most cities experience an upswing in pollen counts in the Spring, Atlanta is particularly terrible. During the Spring months, the city becomes coated in a fine dusting of yellow: cars are yellow; ponds are yellow; shoes are yellow. Replacing small talk of weather is small talk of pollen. Allergy sufferers (if this is a classification of people at all) dread the Spring as much as fashionistos, car enthusiasts, cyclists, and a whole slew of other groups. Pollen is an issue in Atlanta not because it has impact, but because it mobilizes a heterogeneous public to talk, complain, dust off, and otherwise deal with pollen. This is where a project I worked on through the Public Design Workshop (PDW) began.

To start before the beginning, I was part of a group of researchers and graduate students who wanted to engage with the “subjective” aspects of environmental sensing. While many within Science and Technology Studies (STS) would argue that all sensing is subjective, we were not interested in that argument. The STS position explains that sensing (really any work which strives for objectivity) embodies and performs types of views which Donna Haraway labeled “views form nowhere”.1 Objectivity is not facts laid bear, but knowledge produced under a regime of methods, thinking, consenting communities, and complicit objects which all cooperate in a shared belief that the output is, in fact, a fact or truthful. Daston and Galison’s amazing tome “Objectivity” provides a much richer account than I can ever do.2 The point is that my cohort at PDW were not interested in this meaning of subjectivity, but a more colloquial one: accounts of sensed things that escape quantitative measurement. We chose pollen precisely because pollen is measured, but such measurements seem to capture very little of the living with and in pollen.

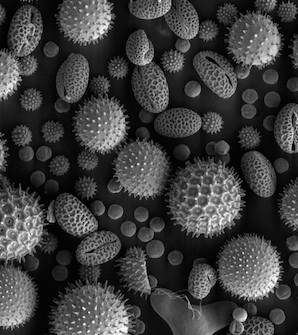

Pollen is measured in a surprisingly literal way. Pollen count—the official number which corresponds to the gross particulate saturation of pollen in the air—is done through counting pollen. Using some collection devices (there are several), pollen is gathered from the air. These collected particles are then counted each day by an individual gifted in identifying types of pollen (trees, grasses, and weeds) and mold amongst a variety of other particulate matter. After gazing through a microscope and tallying marks, the day’s pollen count is reported (which corresponds to the previous day’s pollen release). So, the measurement of pollen results in a number called pollen count, which is literally a count of pollen particles. This description simplifies matters a bit, but illustrates an important point: pollen count has little to do with daily encounters with pollen.

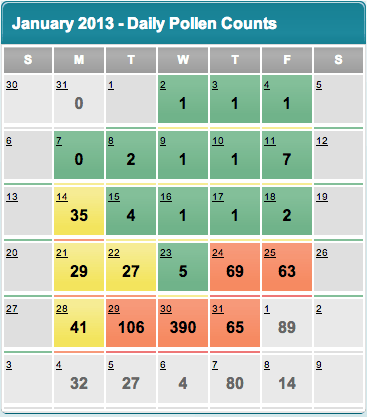

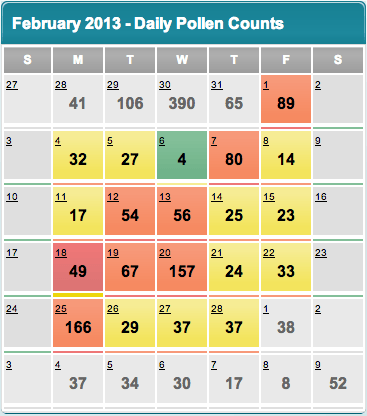

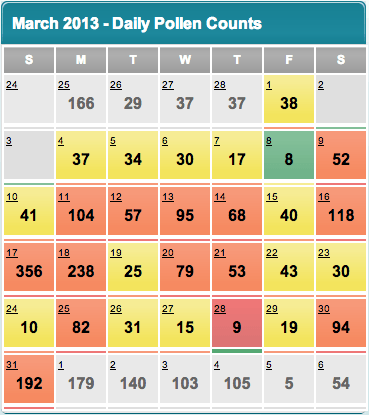

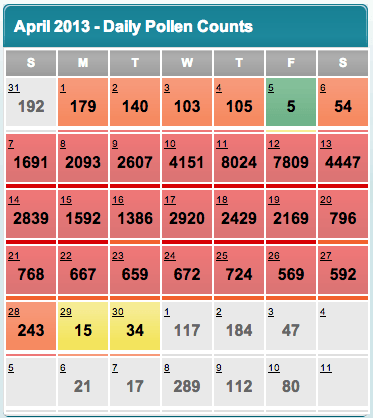

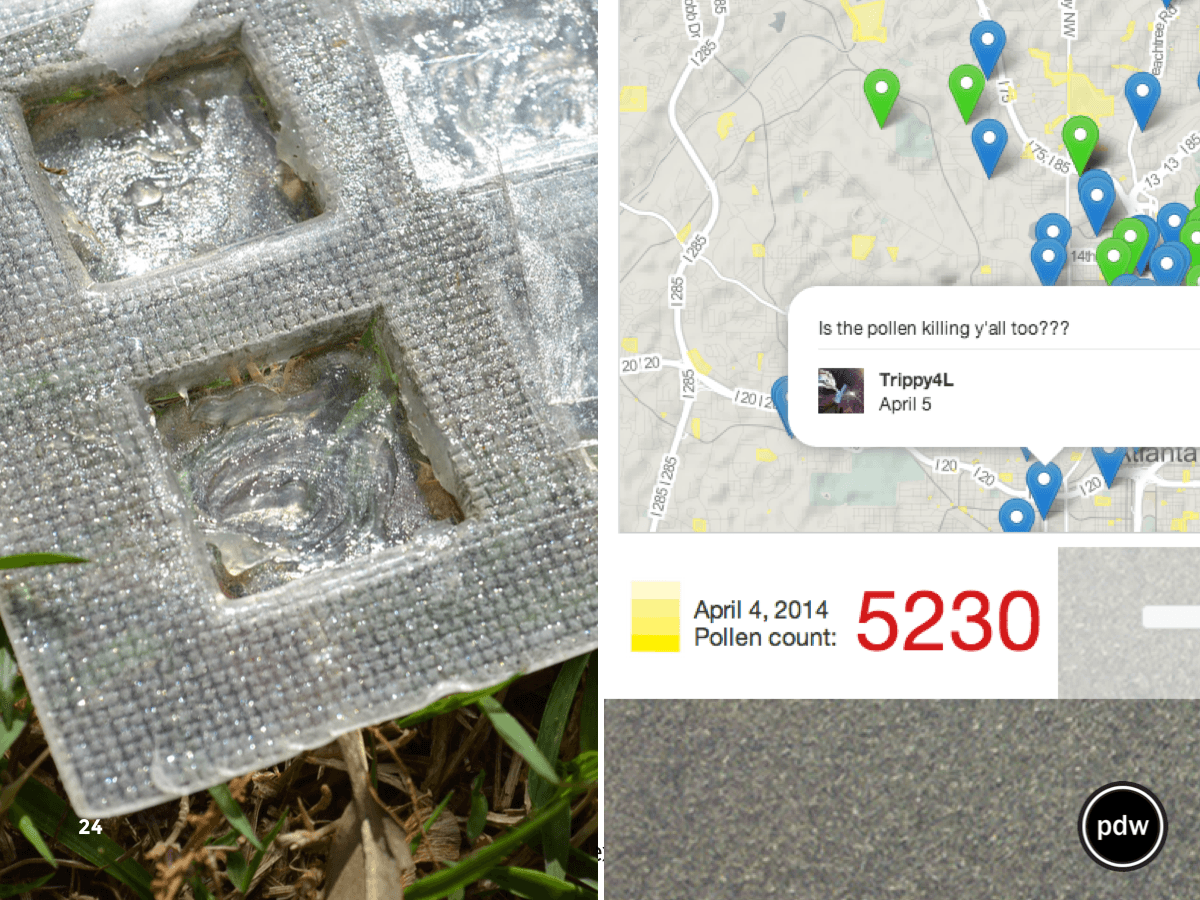

After pollen has been counted, it is classified; here we begin to see some way of translating a number into something useful. There are four standard categories of pollen count—low, medium, high, and extra high—which correspond to four buckets of values—[0-14], [15-89], [90-1499], [1500+], respectively. These classifications are standards used by the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology’s National Allergy Bureau. As is apparent, these buckets are not of equal size. The high classification, for example, spans two orders of magnitude; the extra high is an endless range. While these classifications may be meaningful in some scientific way (I assume only because they exist), they fail to be meaningful other than in an arbitrary way to everyday people. This is very apparent as pollen often greatly exceeds the extra high classification (fig 1) for Atlanta. A pollen count of ~2000 and ~8000 are both extra high, but calling them both extra high is not really very helpful.

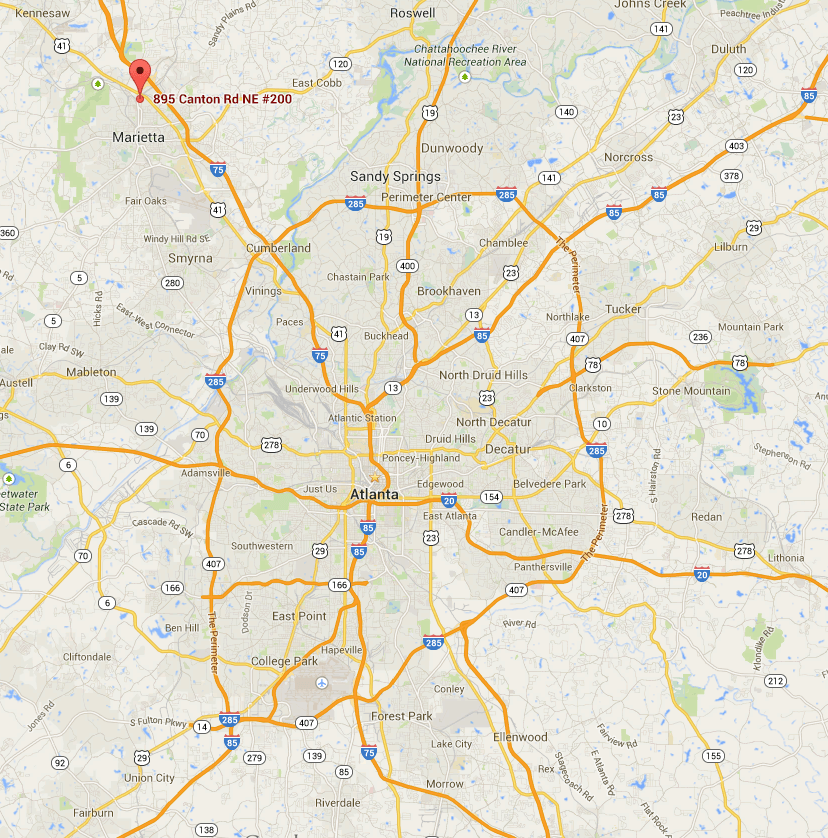

Before moving on from the set up, one last point needs to be addressed: the pollen count for Atlanta is not actually in Atlanta; it is in Marietta. While Marietta is certainly within metropolitan Atlanta, to those living inside the perimeter (the ring formed by I-285), Marietta is outside the perimeter and thus outside the city.

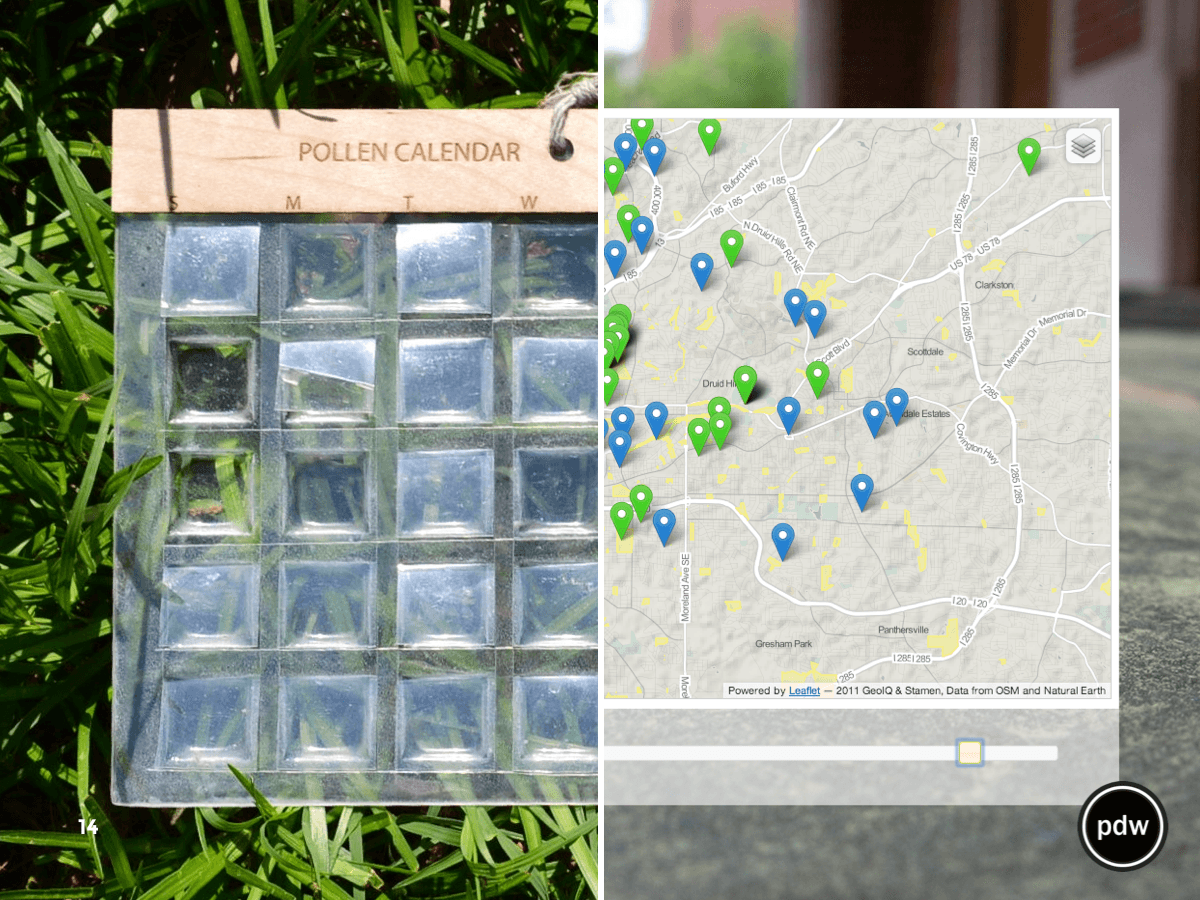

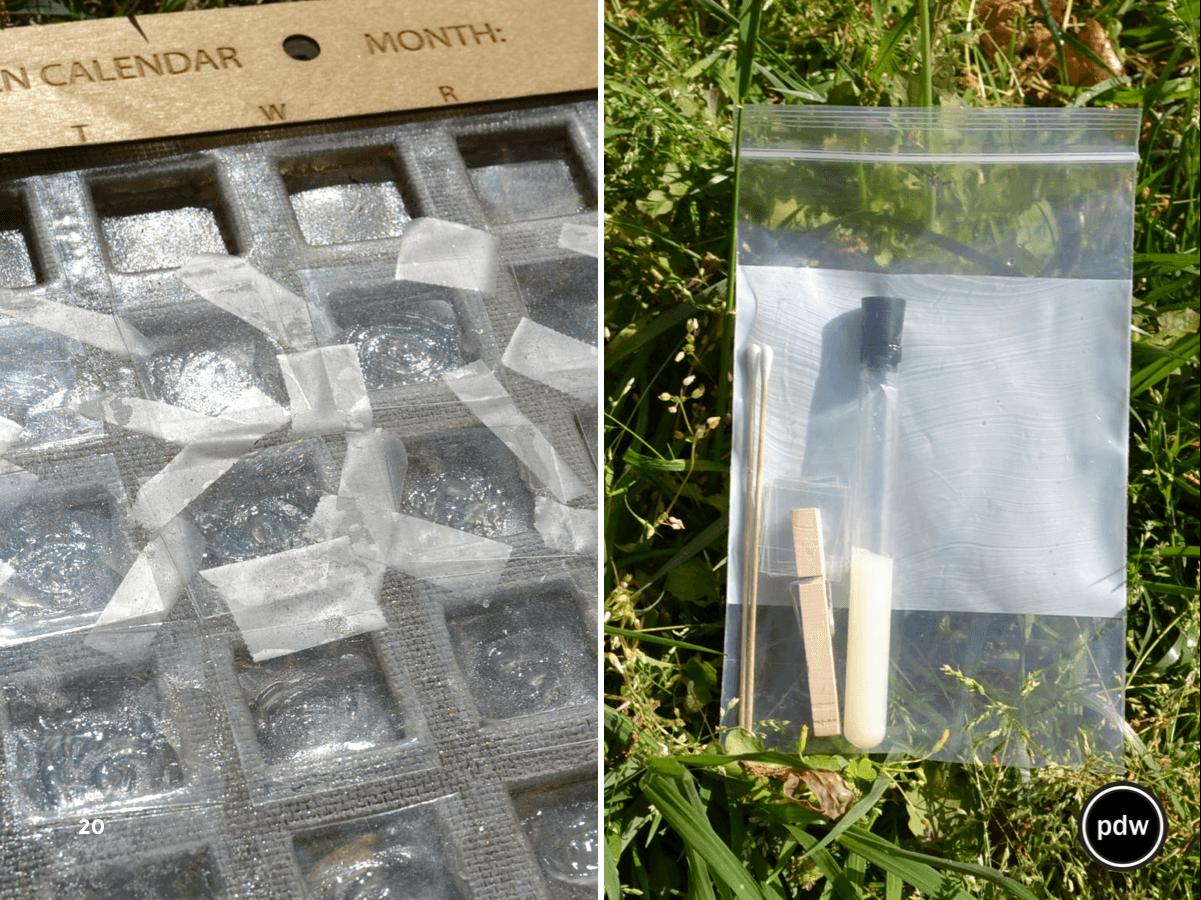

In all these ways, we began to think about pollen differently which resulted in our research-through-design inquiry. In brief, we made two things: 1/ a map which collects mentions of pollen from Twitter and images of pollen from Flickr; 2/ a 35-welled pollen collection calendar. The map requires tweets and images to be geotagged in order to be placed. The collection calendars requires one to place a dap of petroleum jelly in a well, leave the calendar outside, and seal the well with an acetate film at the end of the day (also, repeat). I will stop here, and skip many of the details of the design process and project itself (if you are interested, more can be found here). What I want to focus on underlies this project (and all of our projects for that matter): participation.

Participation is a difficult thing. It requires some form of complicitness, conspiracy, mutual benefit, or alignment. In the Pollen Project, we need people to participate to render the map and calendar relevant. People need to tweet about pollen, but also geotag their tweets to get them on a map. For the calendars to work, people need to collect as much as remember to collect. Even with these two very different modes of participation, it is not so simple. In a second iteration of the map in early 2014, we found it harder than in 2012 to find mentions about pollen that were geotagged. Maybe post-Snowden Atlantans have locked down their traces on the web; maybe Twitter fell out of relevance since the original deployment was in 2012; maybe pollen was less important suddenly. Whatever the reasons, the point is simple: participation is not isolated. To participate in sentiment aggregation is not suddenly the only way in which someone is participating in the world. Even I found it difficult to tweet with geolocation activated. My excuse was default settings on a new iPhone and tweeting through a third-party application (geotagging needs to be done in Twitter to be accessible through Twitter).

People are not the only participants to blame; pollen must also participate. The Pollen Calendars made this very apparent. While pollen covers Atlanta in the Spring, it is hard to collect. Placing the calendar outside often resulted in little to no pollen in a well. While this wasn’t exactly the point (we wanted people to engage in a routine of collection regardless of what is collected), the stubbornness of pollen indicates that it too has conditions of participation. Pollen, like the many other participants—CRON jobs, jQuery, graduate students funded elsewhere, Twitter APIs, and so on—has terms of its participation, and other things it is already participating in that interfere—wind pattern, rain, and temperature fluctuations. Pollen is no more cooperative in this sense then a Tweeter worried about the NSA.

Seems like you should have done more research. Science has got this covered.

Now, it seems fair to blame the project itself for these flaky participants, and I’ll gladly take that criticism. Such criticism is why we do this sort of research: to uncover issues dealing with the formation of publics. Here we revealed tensions internal to notions of proceduralization, publics, and data ‘in-the-wild’. It is not enough, as it turns out, to just collect, or automate collection. Collection assumes standardized participants: obedient Tweeters, docile pollen, regimented calendar operators, and so on. What the Pollen Project did was highlight the need to understand collection more than what is collected. While we were measuring pollen in a direct way, a successful calendar measured the discipline of a person to collect for a month or the skepticism of people with regards to location-aware applications.

Lest one begins to think this is a problem of the participants not being scientists, consider figure 4. Until the upswing of Spring, pollen collection does not take place on the weekends. There is little to report in January for sure, but pollen can still be counted, probably within the Low classification. So our devoted, outside-the-perimeter scientist is as much beholdened to concerns of overtime at the office and family time at home as to counting particulate matter. Participants are busy, and participation is stubborn.