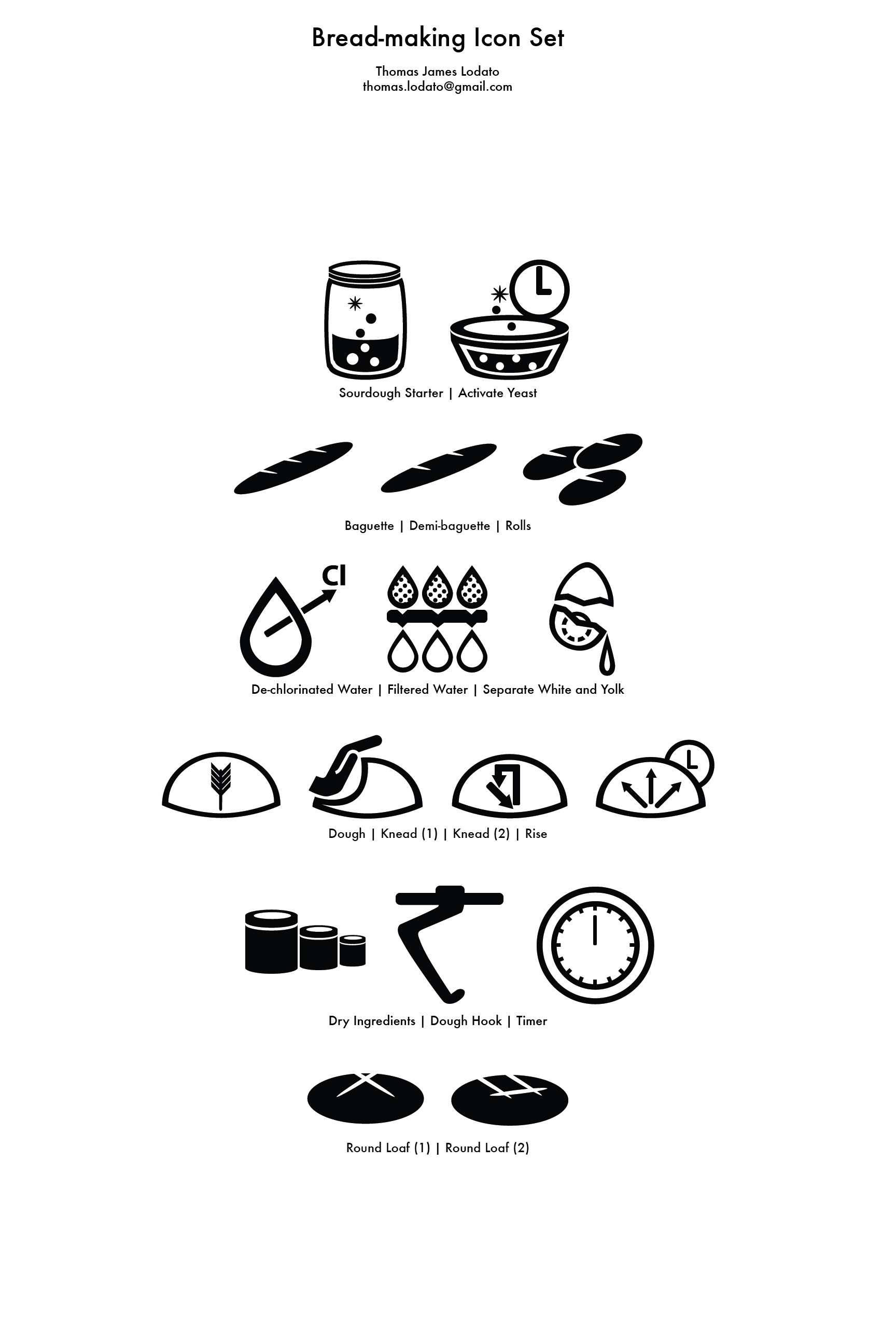

Breadmaking Icons

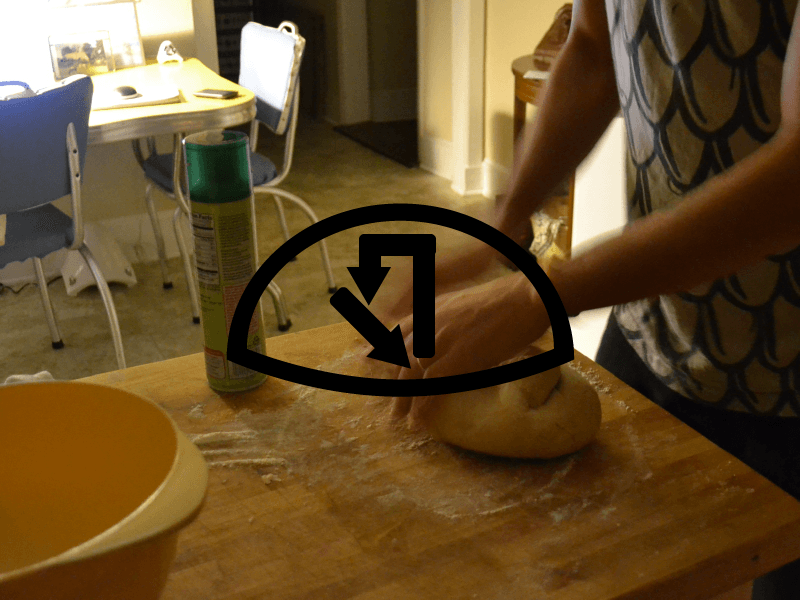

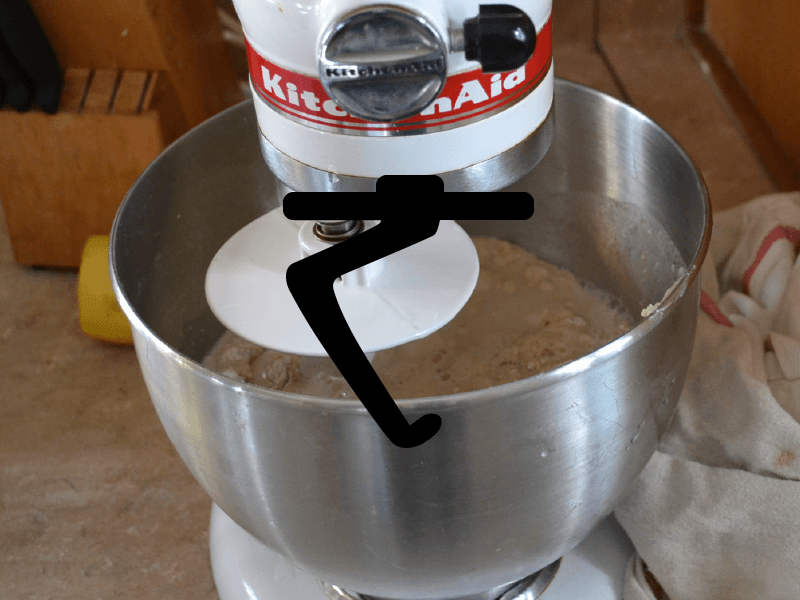

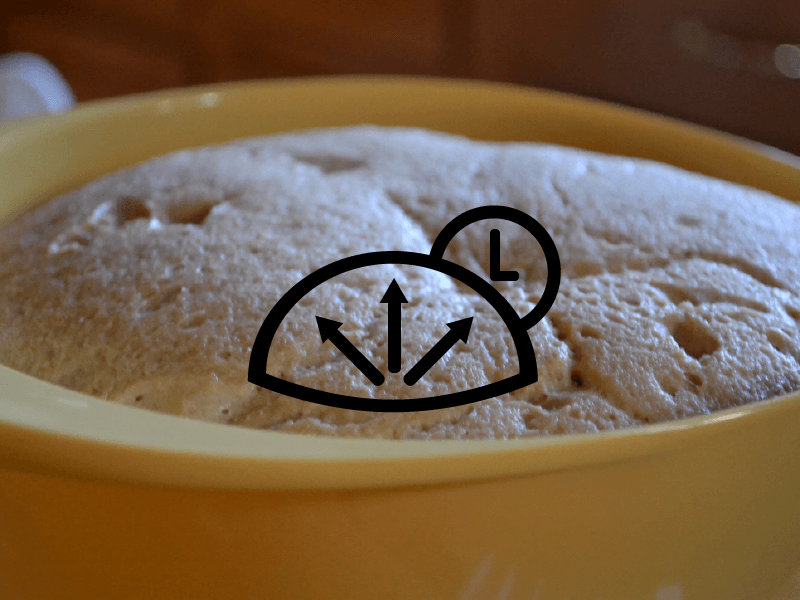

A semester long design research project, I wanted to explore how icon making can be used as a way to understand the worldview of another. I chose bread-making for two reasons. First, we have been exploring how digital technologies may encourage collective and communal activities. Bread, though not a digital technology, has long been at the center of collective and communal work, whether that is in the bread-making process (a collective of bakers, dough hooks, cooperative yeast, ambient temperature, and so on) or in the dining experience (bread as a literal and metaphoric communal object). I wanted to see how translation of these materialities might occur and provide insight into digital practices (see Rosner “The Material Practices of Collaboration“1). Second, bread-making, like many other complex food making processes, is rather opaque. Most people engage with bread as a final product, unaware of how many different actors must be present to realize a loaf. In creating icons, I wanted to offer a glimpse inside the process.

The icon set I developed is an initial pass at this process. While some icons may seem obvious—baguette, rolls, or timer—the goal is to create a litany of iconic objects that populate the world of the bread-maker. This idea comes from what Ian Bogost calls carpentry: a charge for philosophers to create representations of the ontological conditions of the world through the creation of artifacts embodying those conditions. Bogost is, of course, appealing to philosophers who write of the world rather than make objects in it. Designers are not philosophers: they make first and write second, if ever (and often poorly). In a certain sense, designers do the opposite of what spawns Bogost’s concept: designers represent and engage with ontological conditions at their be-ing, while vaguely engaging in what those representations mean of the world and of Being itself. More precisely, designers engage Being in a Heideggerian fashion—Being is lived and precognitive rather than a concept held in beneath a microscope for inspection. The problem with this type of engagement with Being (and why referring to Bogost is important here) is that these representations are simply that—representations—and in no way complete. Bogost is quick to point out that works of carpentry are illustrations of ontological conditions (what it is to be something). Carpentry sets out into making with the notion of partiality and incompleteness–a litany isn’t the whole world but just a glimpse at a different world. Designers, on the other hand, do not necessarily make clear that a representation isn’t the representation.

To return to icon-making, my point is that an icon set is never more than a representation of something, such as bread-making. This is not to say that it is less worth attention since it is, by its nature, partial or representational. Instead, the partiality of icon sets is why they are worthwhile as a design research project. Repositories, such as The Noun Project, provide a prime example. The Noun Project’s charges itself with “building a global visual language that everyone can understand [and so] enable our users to visually communicate anything to anyone.” 2. The repository fails, for instance, in allowing categories (e.g. “bread”) to partially encapsulate objects. For example, the grouping of icons for “bread” housed two icons (for a while): a baguette and a round-top pan loaf. What about naan? Or, lavash? Does “bread” even accurately categorize what these flour-based foods are culturally or functionally? These types of repositories, whether or not they have anything to do with digital media, are certainly shifting the reach of designed things and associating the rhetorics of universal design with a new type of digital colonialism (insensitive to local conditions as much as flying under a banner of morality). In exploring icon-making through bread-making, one begins to see these gaps.

The icons then do two things: for bread-makers, they are validation of bread-making through a means of communication; for non-bread-makers, they are wondrous objects that encourage interrogation of the relationships amongst parts. While the icons on their own seem to purport ”This is bread-making”, as a design research project one must be careful to identify this set with my experience.

But, why icons? On the outset, I wanted to limit the output to focus on the design process. Icons were an arbitrary choice, though a classic output for design. Simply, designers make icons sometimes, and this is one of those times.