What is public?

The following is an edited transcript of a position statement I presented on a panel on public space design. The panel took place on April 21 at the Center for Civic Innovation in Atlanta, GA. The panel was gathered because of concerns around inclusiveness within the built environment. The panelists came from backgrounds in city planning, sustainable development, community organizing, and architecture. Underlying the stakes of the panel was the term “the public,” which I have spent a great deal of time considering. As such, I wanted to unpack the term “public” in terms of participation, inclusion, and legitimacy within the planning and development of public space.

–

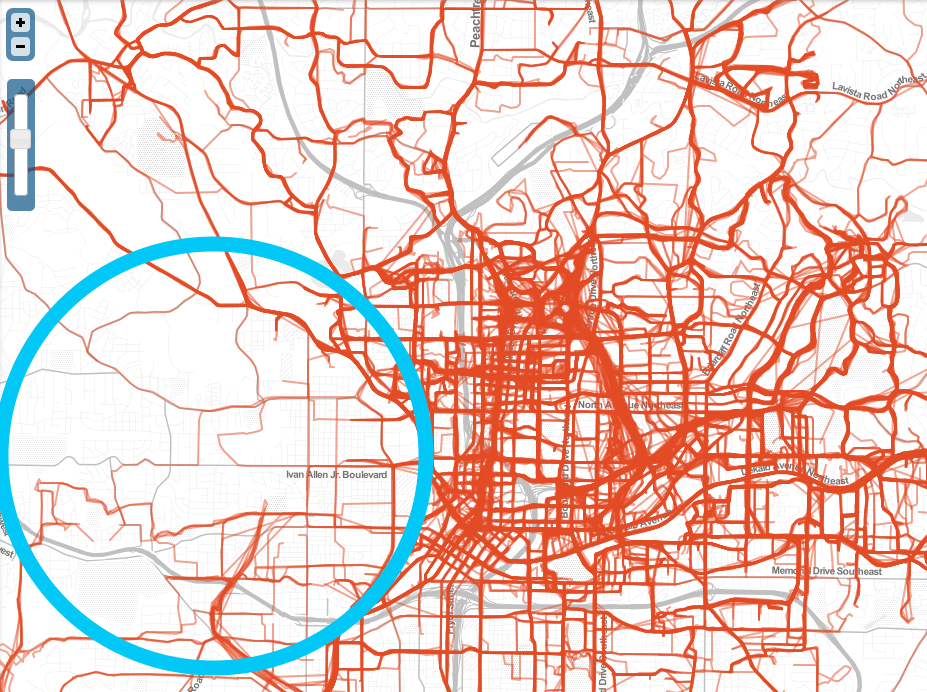

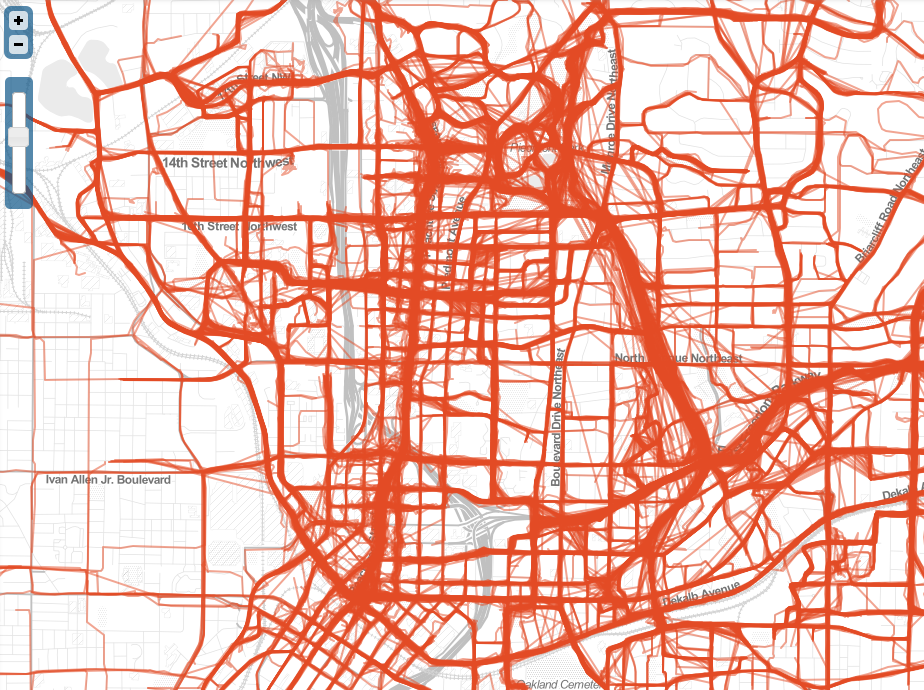

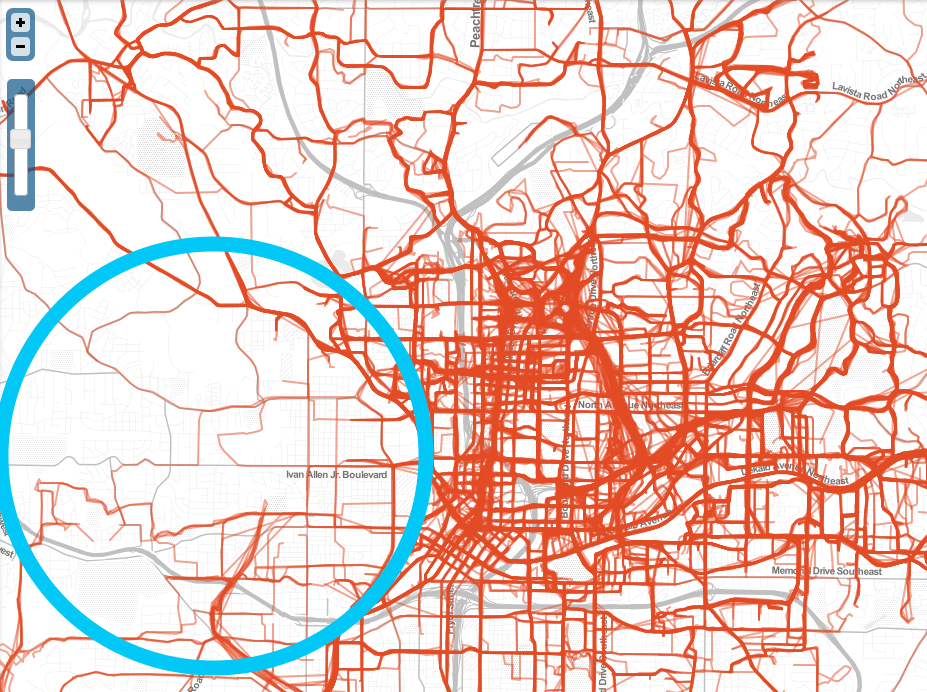

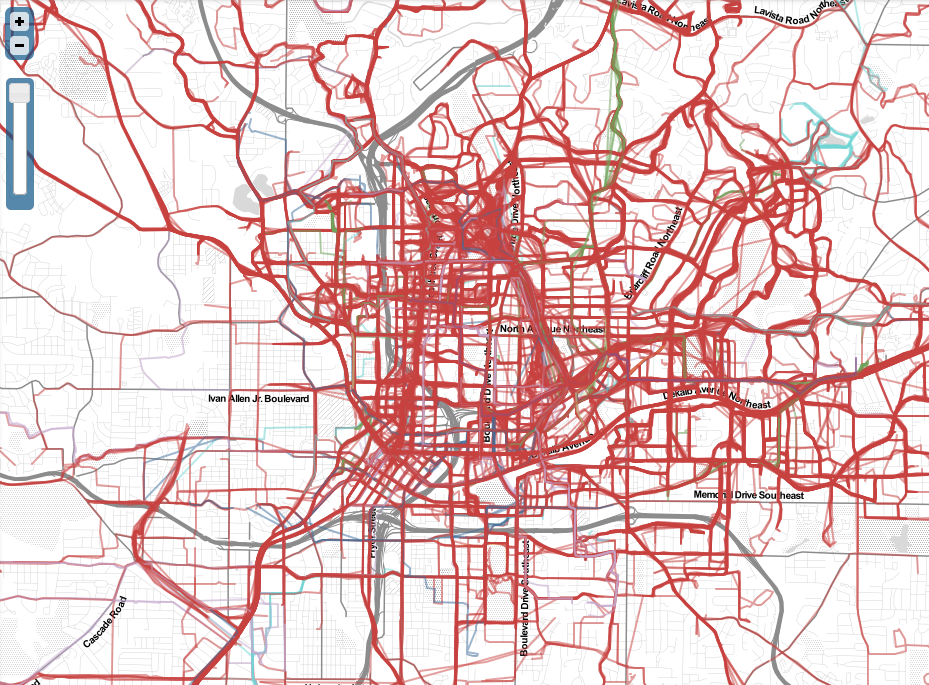

The CycleAtlanta map was created, in part, by two of my colleagues in the Digital Media program at the Georgia Institute of Technology: Mariam Asad (a third-year PhD student) and Chris Le Dantec (an assistant professor). The CycleAtlanta map uses an Android and iPhone application to log bike rides through the city of Atlanta. Individuals are able to indicate their age, ethnicity, the purpose of their trip, and their comfort riding. The application, map, and the underlying data partnered with the City of Atlanta to help city planners make decisions around transportation infrastructure. As such, the application provides a way for cyclists to participate and advocate for infrastructure by showing where they ride. The thick vertical line on the right of the map (figure 1: left) is the Eastside Beltline trail and the thick intersecting horizontal line is the PATH. In the center of the image, the thick vertical line is Peachtree Street.

When we zoom out of the map, we see something else too (figure 1: right). The area circled in blue is the historic Westside of Atlanta. As many people know, the Westside neighborhoods are densely populated and many people in these neighborhoods ride bikes. The question that needs to be asked is why are so few paths shown? While anyone can use the CycleAtlanta application, anyone does not mean everyone; this difference is what I want to unpack about the term “public.”

Within the bounds of the map, participants abide by certain criteria. First, to participate, one must own a smartphone and ride a bicycle. While this observation may be obvious, it already presents conditions in which not everyone can be represented on this map. More importantly, other criteria exist that are implicit and present other issues: individuals must be willing to be surveilled and individuals must believe that their input will lead to systemic infrastructural changes. This latter point is something that is the biggest barrier for participation as the new Falcon’s Stadium can attest.

The CycleAtlanta map and application demonstrate that participation in public things is not flat. Even if we begin with the premise that anyone could participate, not everyone does and, most certainly, not everyone is considered legitimate according to the criteria of participation. While cyclists need a smartphone, they also need to feel that through the inscribed mode of participation (e.g. data logging) their contribution matters. Alongside being a participant are the terms of participating. As such, who is legitimate and the legitimate conditions of participation are matters that should be of deep concern to city planners and designers.

In 1927, American pragmatist philosopher John Dewey wrote a book call “The Public and Its Problems.” In this book, Dewey was trying to understand what role the public had within contemporary politics. The book responds to another text written by Walter Lippmann (“The Phantom Public” [1927]), who argued that public entered political discourse when elected officials could not settle an issue. Lippmann claimed that the public were arbiters. In response, Dewey sought a more optimistic notion of the public. For Dewey, “the public is a political state,” [35] meaning that a public refers to a specific set of interests rather than all interests, all together. As representatives, elected officials speak to the existing interests of positions and people they represent. In this line of thinking, a public and an issue mutually arise. Dewey wrote,

“The public consists of all those who are affected by the indirect consequences of transactions to such an extent that it is deemed necessary to have those consequences systematically cared for.” [15-16]

In this statement, Dewey rejects that public things, like public space, are public because of who they are for, namely everyone or anyone. Dewey is not saying that space (or any public thing) shouldn’t be for everyone, but instead fundamentally not everyone is given equal representation in the making and use of public matters. In this statement, Dewey is claiming that the way consequences of decisions are cared for is what makes something public. According to Dewey, things, like space, are public because of who participates in making public things, both directly, as designers and representatives, and indirectly, as represented parties. Thus, the notion that the public is anyone or everyone fails to address the underlying issues related who gets to legitimately participate and how participation is deemed legitimate. Dewey’s pragmatist notion offers a starting point that does not assume conditions called public are other than this differentiated representation.

If space is public because of who participates, then the question is who participates?

With the CycleAtlanta map, who participates are largely white men with smartphones. As an example, the CycleAtlanta map and application is not a critique of my colleagues. Their work as part of the Participatory Publics Lab has long engaged the Westside neighborhoods with other means of participation and inclusion. Instead, the CycleAtlanta map demonstrates that the public does not mean everyone and anyone. Moreover, the map shows that introducing technological means to increase participation does not necessarily mitigate the underlying barriers to participation (and may instead reinscribe them).

For designers and planners, initiating new relationships and overcoming existing barriers begins with rethinking the terms of designing. Public space begins with participation in the design process, and to discuss inclusiveness in design objects comes from inclusiveness in designing such objects. In instances where design or city planning attempts to make something public, whether that is public space or public transportation or public opinion, there is a great deal of responsibility to attend to what public is being inscribed and what inscription mechanisms are set forth. If designers and city planners are unable to offer new ways to reach communities, and give legitimate representation to these communities, then the public being designed (for) will represent the status quo.

Taking this view of publics seriously means starting design work with two core questions:

Who can legitimately participate in the production of things we call public?

And when people are invited in, does the design process offer ways to legitimate participation that are typically un-/under-represented?