Three Positions on Civic Hacking

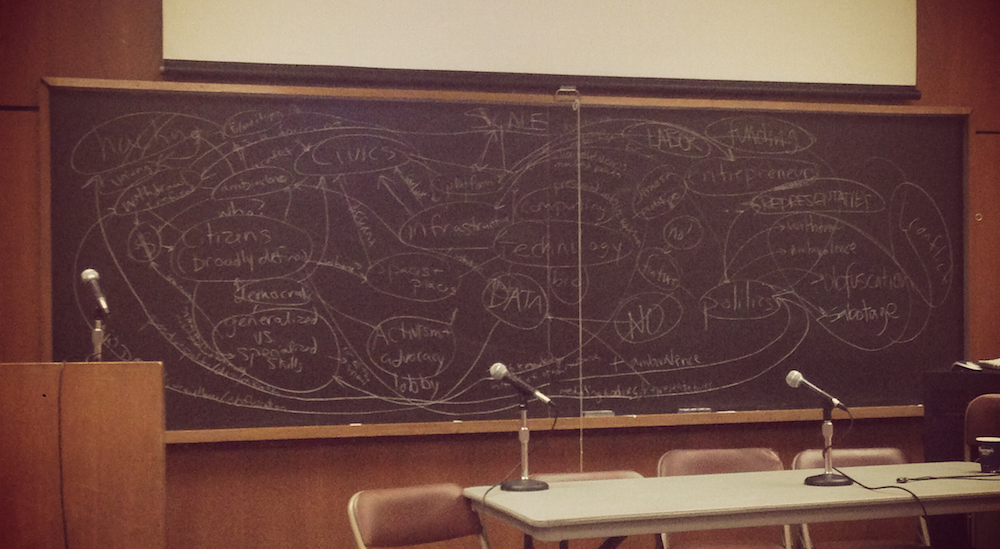

The following are positions presented at the Digital Labor Conference (November 14-16 2014 at The New School, NYC). The positions come from my continued research on issue-oriented hackathons. These positions were part of a panel on civic hacking, which included contributions from Carl DiSalvo, Melissa Gregg, Max Liboiron, Lilly Irani, and Andrew Schrock. The presentations were aimed at being debates over terms found at civic hacking events (mine being civic hacking, participation, and speculation). Each position was to be no more than 3 minutes. Audio for the panel can be found here

There is no such thing as civic hacking

There is no such thing as civic hacking. What we currently call civic hacking primarily means creating software applications and computing infrastructures. These creations aim to manifest future conditions that offer new modes of engaging with and across governing bodies and each other. In the rare instances these project actually make something beyond a GitHub repository, civic hacking is not what occurs at civic hackathons. Civic hackathons fundamentally assume the same civic orientation—that of technological citizenship. Technological citizenship transforms a person into a citizen insofar as she is a user or entrepeneur, and transforms political representation into mere representations of politics. Civic life, at these events, is but an information problem.

There is no such thing as civic hacking. What we call civic hacking is partial. It is a confusion of “design will and intention,” to use terms from design scholars Nelson and Stolterman. Design intention and will combine aims and constraints with their execution. Intention is a priori and will is ad-hoc and post-hoc. Intention is the craft of arguing for a future; will is the ability to make it. Design intention is about making matters concerned; design will is about making concerns matter. Civic life is more than intention and imagination–it is a product of living and not just of proposing living.

There is no such thing as civic hacking. At civic hackathons, civics are too-often seen as untapped markets for opportunistic entrepreneurs. These projects sate the neoliberal status quo, and push evermore toward private, profit-driven public life. Worse yet, some claim this work frees us with yet-another technological revolution. But free us from what, Chris Anderson? Apparently, from compensation. Spec work is the engine of the technocracy, hackathons are its garage, and entrepreneurs, the mechanics. They say, “This repair is going to cost you.”

There is no such thing as civic hacking. Hack//Meat, an issue-oriented hackathon, offers a glimpse. This event focused on the US meat industry. The winning project, named CARV (spelled with no E), proposed getting rid of the traditional paper-based labels used in independent slaughterhouses. Their final prototype was comprised of some software, a USB shipping scale and a Google spreadsheet—they bragged, “weights can be uploaded automatically!” As such, CARV was barely extensible. In 2014, CARV’s website states1 that the project aimed to, in fact, inspire farmers to find profitable technological solutions. Is this not the stew in the pot calling the kettle black?

Instead, I want to see hacked civics. These hacked civics are beyond user-friendliness, beyond vowel-less ventures, and beyond end-user license agreements. These hacked civics rethink the state; they cobble together various citizenries; they break and reassemble civic life; they don’t agree that the answer is technology; and, most of all, they don’t agree on civics. At civic hackathons, I want to see this civic hacking. I want to see civic hacking that hacks civics.

Participation in/by/through hacking

Participation is not homogeneous, nor is it equivalent across contexts. Participation with respect to matters-of-concern is as much as a factor of intent and execution as it is a factor of time and repetition. Frequently, issue-oriented hackathons are flatly discussed with respect to how they do or do not engage matters-of-concern. This does not respect the subtle differences in modes of participation found at these events. What we need is language to characterize such differences. I offer three terms–participation-in, participation-by, and participation-through. These come from my study of issue-oriented hackathons and refer to the activity of hacking, but can be extended further. To do so, we need to ask how might participation of this sort translate into participation with matters-of-concern?

Term 1: Participation-in, as in “participating in the activity of hacking.” This mode of participation is limited by the time, space, scale, and scope of a hackathon. Participation-in is akin to tinkering, or making for the sake of making. This is the most common mode of participation at these events. Examples range from developing unscalable applications, addressing hypothetical problems, speculating on the existence of data, or treating topics as technical playgrounds. So, participation-in engages matters-of-concern insofar as one situates her actions beyond tinkering. Participating-in almost categorically fails to translate into participating with a matter-of-concern save at the individual level in select cases.

Term 2: Participation-by, as in “participating by engaging in hacking.” This mode of participation embraces the limitations of time and space of a hackathon as constraints to perform scoped and scaled tasks, that is, manageable tasks. Participation-by is akin to batch or group labor. Examples range from creating data APIs or implementing critical features within ongoing projects. Participation-by is either initiated by stakeholders who find volunteers who can address such tasks or by volunteers who can make broad projects into a list of manageable tasks as a plan for present and future work. So, participation-by engages matters-of-concern insofar as a project can be rendered into a litany of manageable tasks and someone is accountable to the completion of these tasks. Participating-by hacking transforms into participating with a matter-of-concern at the project level.

Term 3: Participation-through, as in “participating through the activity hacking.” This mode of participation uses the limited time, designated space, narrow scope, and local scale of a hackathon to prototype social arrangements. These prototypes formulate, negotiate, and contest issues. Participation-through is akin to the design workshop. Examples range from concept mapping or discussing plans of action, both of which are done with relevant stakeholders. Participation-through allows individuals and groups to simulate matters-of-concern. These simulations can be thought of as prototypes of publics—what I call proto-publics. So, participation-through engages matters-of-concern insofar as the events are documented and foster new conversations, and relevant stakeholders attend and assume the role of participants. Participating-through hacking transforms into participating with a matter-of-concern at the organizational level.

On Speculation and Spec Work

Speculation constitutes the basic assumption of what designers do. Design theorist Herb Simon is often cited,

“Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones.”

Designers then speculate on a preferred future, one that can only be argued for rather than proven. Certainly we can critique Simon for his use of the term preferred—I mean, preferred for whom?—but I want to focus on Simon’s and others’ embrace of the term speculation.

While the term speculation doesn’t trouble the designer, the term spec does—spec as in speculative work. Spec work refers to design work that is done prior to a formal contract, statement of work, or payment scheme is established. These are off-the-books activities accompanied by the promise of being on them, I mean, assuming the work is good. Designers are cautioned about spec work by guilds and groups: Freelance Ain’t Free.

Issue-oriented hackathons struggle with speculation and spec work. They require free work and promise an eventual pay-off, whether that is a better life or a better profit. Some examples illustrate the tension of speculation and spec work further.

Food Data Hack provides the first example. The event focused on land use and food access in Atlanta, Georgia. One group proposed an online map of the available resources in the resource-scare Westside neighborhoods. This work was picked up by one of my collaborators and brought to the 2013 National Day of Civic Hacking. There it was co-opted by a private organization and developed to aid in their fundraising.

EcoHack3 provides the second example. In a poorly insulated former Pfizer building in Brooklyn, I worked with an entomologist from American Museum of Natural History. I cleaned and uploaded bug notes. At other tables were designers, developers, scientists, and subject matter experts; all were there working on their weekend. They gave their time and skills; they received bagels and pizza as payment.

Hack//Meat is a third example. Where the previous events had no criteria for winning, Hack//Meat offered VC funding to the best entrepreneurial idea. This model is, in fact, very typical of hackathons in general. At issue-oriented hackathons of this sort, issues are attended to insofar as there is a viable business plan. Obviously, some issues are left out, and much of the work is on spec.

These example illustrate that the tension of speculation and spec work is not just a debate over payment, but of value and value for whom. As a design researcher, I am full of questions:

How can these ideas be made and not be made private?

What is payment for volunteering beyond pizza?

Why not seed new political representatives rather than new entrepreneurs?

This is the crisis of speculation: with the future indeterminate, we want to compare options. But, generating these options is work we struggle to value. I have co-suggested elsewhere that the work of civic imagining is important, and it is. Civic imagining builds language and expectations of the world we participate in. But can we speculate on civics without speculating on work? The first step is we must stop using the eventuality of these speculations as excuses for why the work unpaid—work is work. I suggest that civic hackathons need a different type of speculation: not what future do we prefer? but to what future are we actually willing to commit?

-

“We are currently working on applying for grant monies to support our research so that we can help farmers and processors fully utilize existing technologies, scales and inventory programs. Our hope would be to publish our findings and possibly turn them into an educational site where we share existing solutions and inspire farmers and processors to share their data and find technology solutions that would make their businesses more profitable. If no such solutions exist, we would love to work with start-ups or established software companies that could help us with capturing data points that can be utilized by all members of the value chain.” carvhack.org ↩