Georgia Smart Communities Workshop

The Georgia Smart Communities Workshop was an event designed to better understand the needs, opportunities, and barriers to local governments implementing pilot technology projects (often called “smart city projects”) across the state of Georgia.1 The workshop served two ends:

- Educating local government stakeholders about smart communities

- Assessing the viability of a state-wide pilot program

With these two goals in mind, the event served as both an outcome (for educating) and a methodology (for data collection). The event brought together a variety of local government employees,2 who learned from local and national experts, as well as one another. These experts provided definitions, state and national best practices, and case studies of successes and failures. Through structured and unstructured programming, participants discussed ideas in small groups. As a means of data collection, the activities before and during the event provided quantitative and qualitative data that helps us understand what local governments were facing in launching a pilot. From these data, we sought to establish empirically-informed terms, conditions, and requirements for a state-wide technical assistance program to support smart community pilots.3

The following documentation gives an overview of the design of the Georgia Smart Communities Workshop, with an emphasis on the ideation activity that took place in the afternoon. This latter portion of the workshop engaged participants in activities used to gather data while educating local government employees about design thinking. In this case study, the term we refers to me (as lead designer) and Carl DiSalvo.

Additional information about the workshop can be found here.

Final Schedule of Events

| Time | Activity | |

|---|---|---|

| 11a | Welcome | |

| 11:10a | Keynote | |

| Sokwoo Rhee, Associate Director of National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Best practices on smart cities from around the US from Global Cities Team Challenge | ||

| 11:30a | Panel | |

| Lt. Keith Lingerfelt, Gainesville Police Department; Professor Ellen Dunham-Jones, Georgia Tech, School of Design; Mayor Dan Ponder, City of Donalsonville; Abe Kani, Gwinnett County, CIO/Director of Information Technology Services; Cynthia Curry (moderator), Director of IoT Ecosystem Expansion, Metro Atlanta Chamber of Commerce | ||

| 12:30p | Lunch | |

| 1:30 | Ideation Activity: Define + Specify + Propose | |

| 3:30p | Closing + Next Steps | |

| 4p | End |

The Design of the Workshop as a Methodology

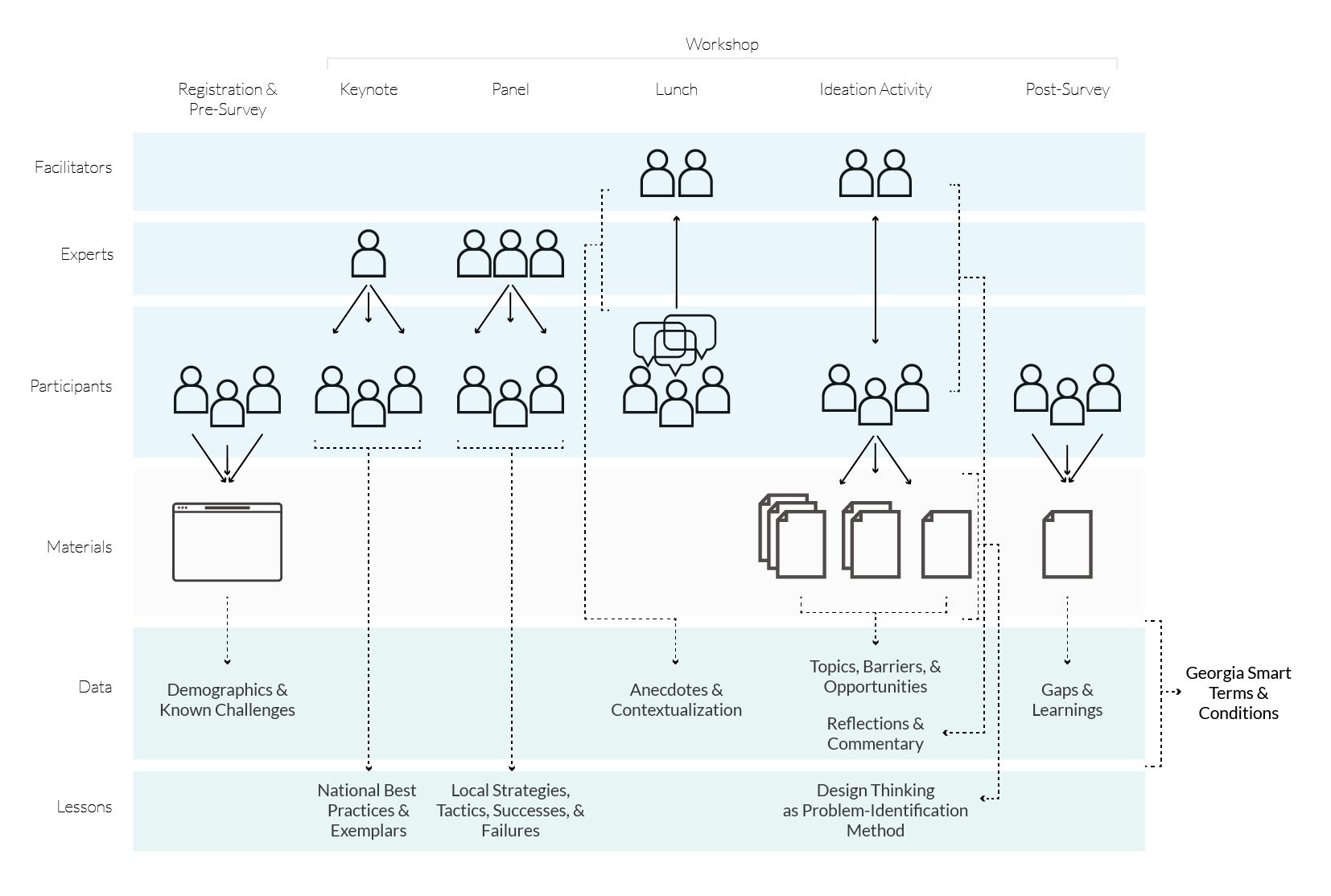

In planning this workshop, we mapped out the various moments in which participants could be engaged and data could be collected (see Figure 1 (hi-res)). Using the workshop as a methodology required that we find ways to document explicit comments and concerns as well as trace tacit assumptions, aspirations, needs, and barriers. As such, we were responsible for designing two aspects of the workshop: the roles of the facilitators (namely us) and the data collection materials (surveys and an afternoon ideation activity).

Pre-Workshop Data Collection

Where the actual workshop constituted the educational opportunity, data collection started prior to the event. From the basic information collected during registration, we were able to correlate sign-ups with census data about city and county governments. We compiled federal census data on population size and growth, landmass (e.g. size of the jurisdiction), educational attainment, income and poverty rate, and labor force and unemployment rate. Additionally, based on registrants title and departmental affiliation, we created aggregate statistics related to domain knowledge and position within government (or outside of it). These data provided a baseline for our discovery process of terms and conditions.

As is standard protocol for running a workshop, we sent reminders about day-of logistics (e.g. where to park, directions, and schedule of events) to participants a few days prior to the event. In tracing the points of contact between us and participants, we saw this reminder email as an opportunity to circulate a pre-survey to drill deeper into why participants were attending. The pre-survey was hosted on Google Forms and asked how knowledgeable participants were of the topic (smart communities/cities) and what local challenges motivated their interest in attending. We had a response rate of about 42%. This second batch of data helped inform the afternoon activity.

Ideation Activity: Define + Specify + Propose

On the outset, the afternoon activity was loosely defined. The goal was to collect data about the state of smart communities across Georgia. Given the two goals of the workshop—education and data collection—we felt the afternoon activity should also serve as an educational opportunity. Rather than educate participants through a talk or panel, the afternoon activity would educate through hands-on experience.

Based on our previous work doing public workshops (such as GrowBot Garden), we set a constraint that the afternoon activity should focus on ideation without engaging in methods unfamiliar to the participants. From experience with local government stakeholders, activities such as sketching, low-fidelity prototyping, or other constructivist activities required high engagement with facilitators. With only two facilitators staffing the afternoon, these activities weren’t feasible. As such, we decided to employ a worksheet-based design thinking activity that walked participants through a process of ideation and refinement. This process, though common for designers, is fairly novel in the context of local government. Additionally, the afternoon activity was allotted only two (2) hours, which meant that in order to explain the activity, model it with an example, and allow time for sharing, the activity needed to be approximately an hour long.

The process of designing these materials defined the roles of the facilitators at the workshop. As a design activity, the task was ultimately a combination of graphic design and layout, copy-writing/editing, and interaction design (as in the ways the worksheets get used and facilitators intervene).

Pass One

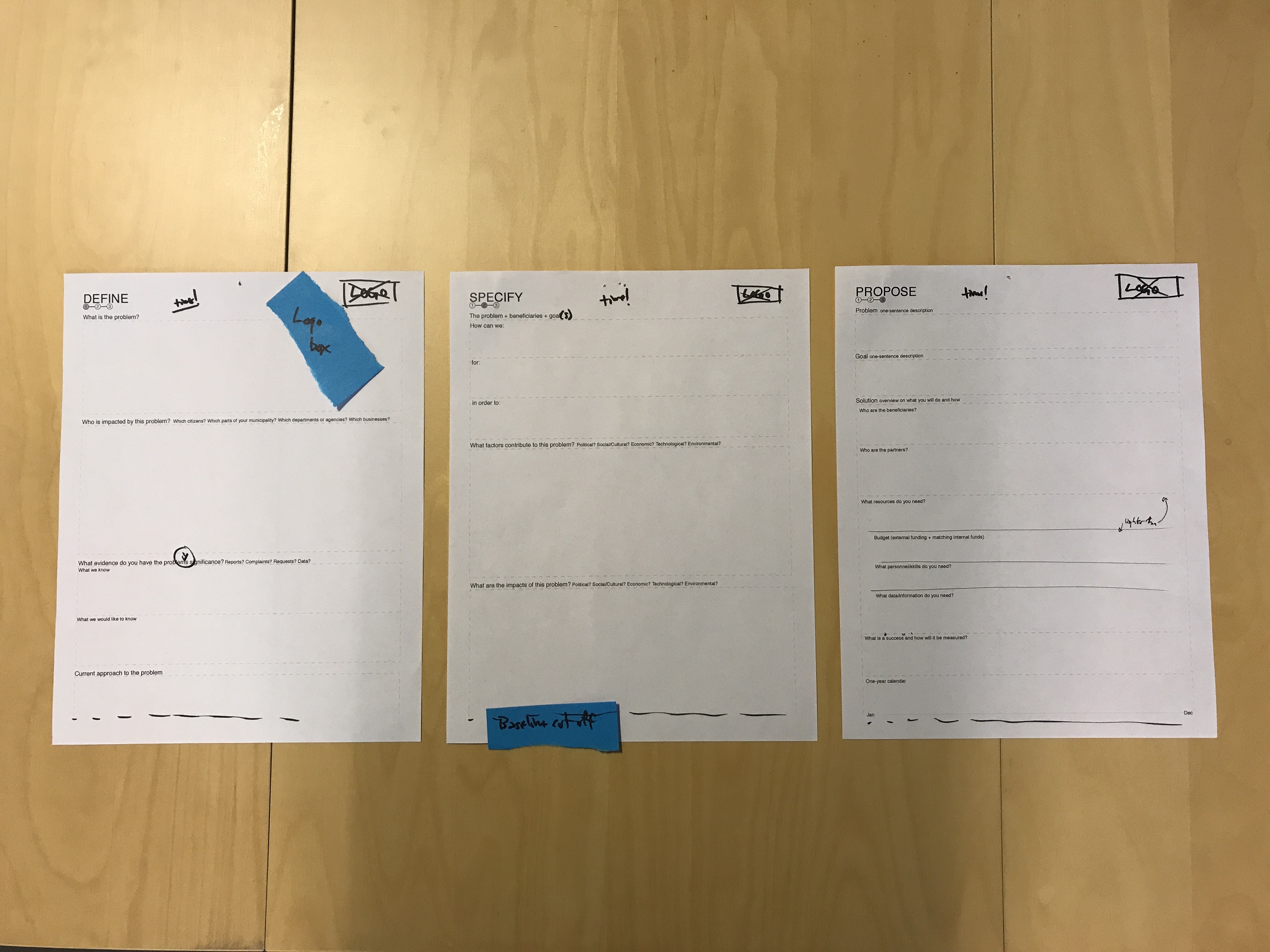

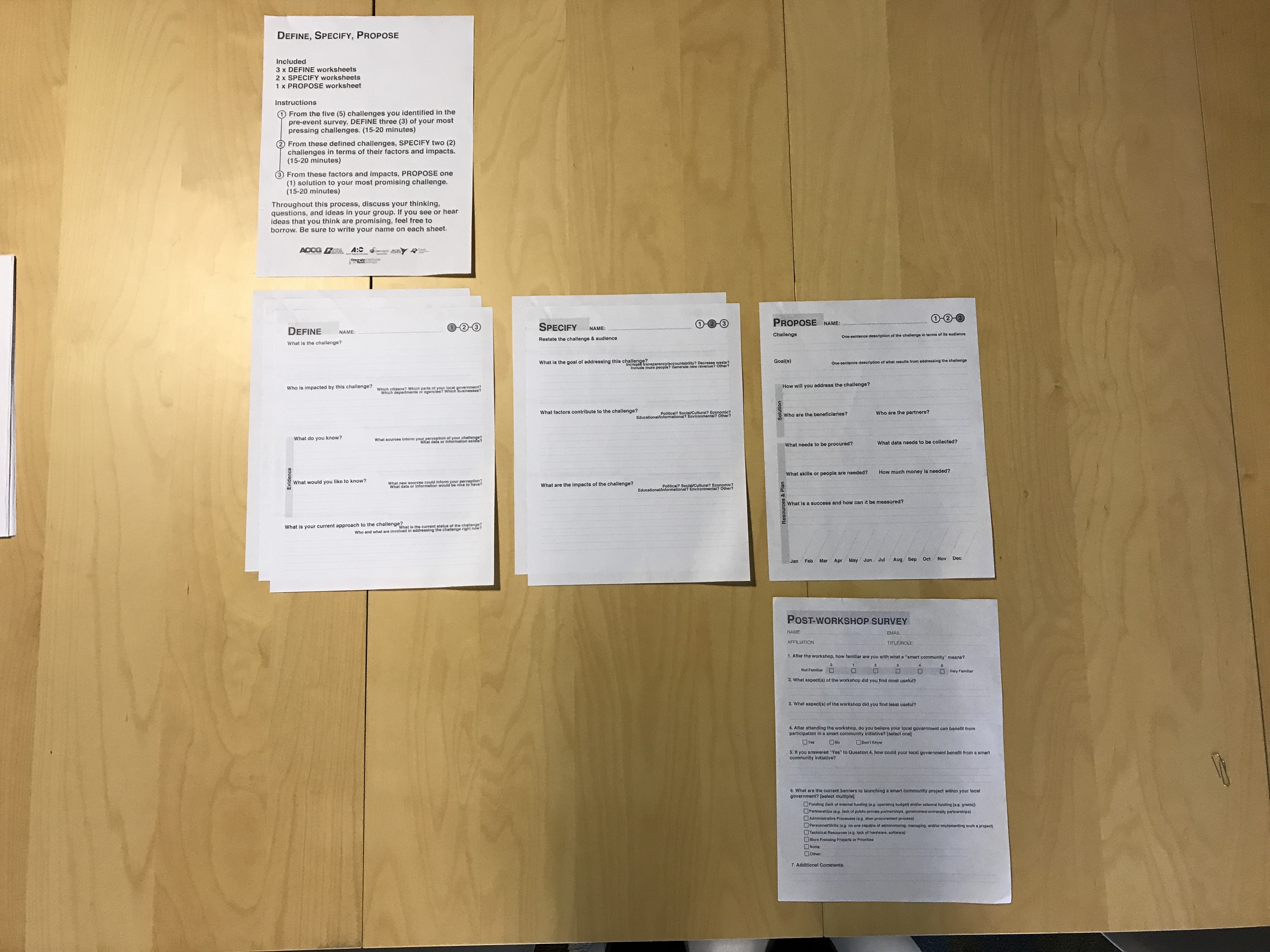

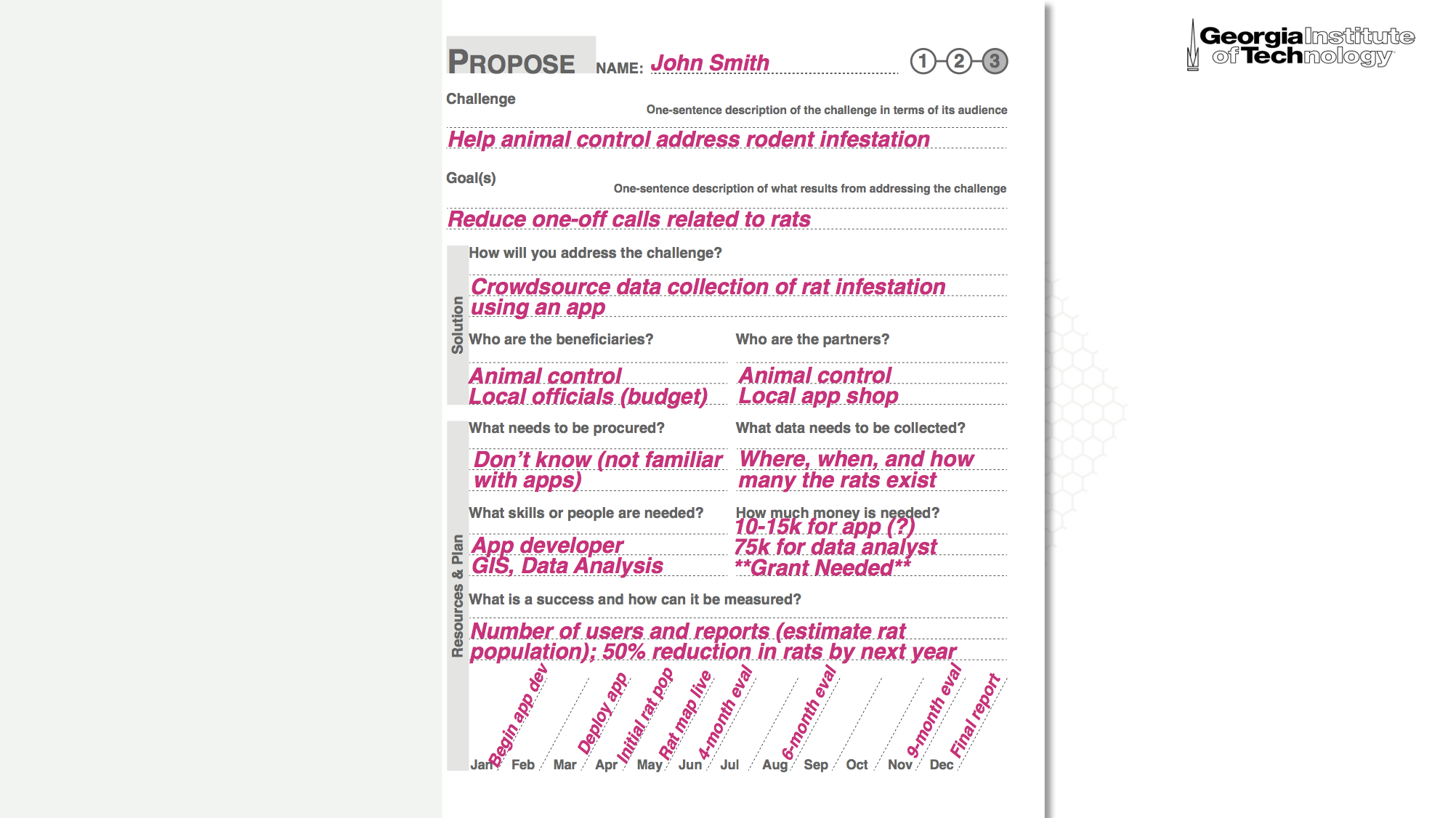

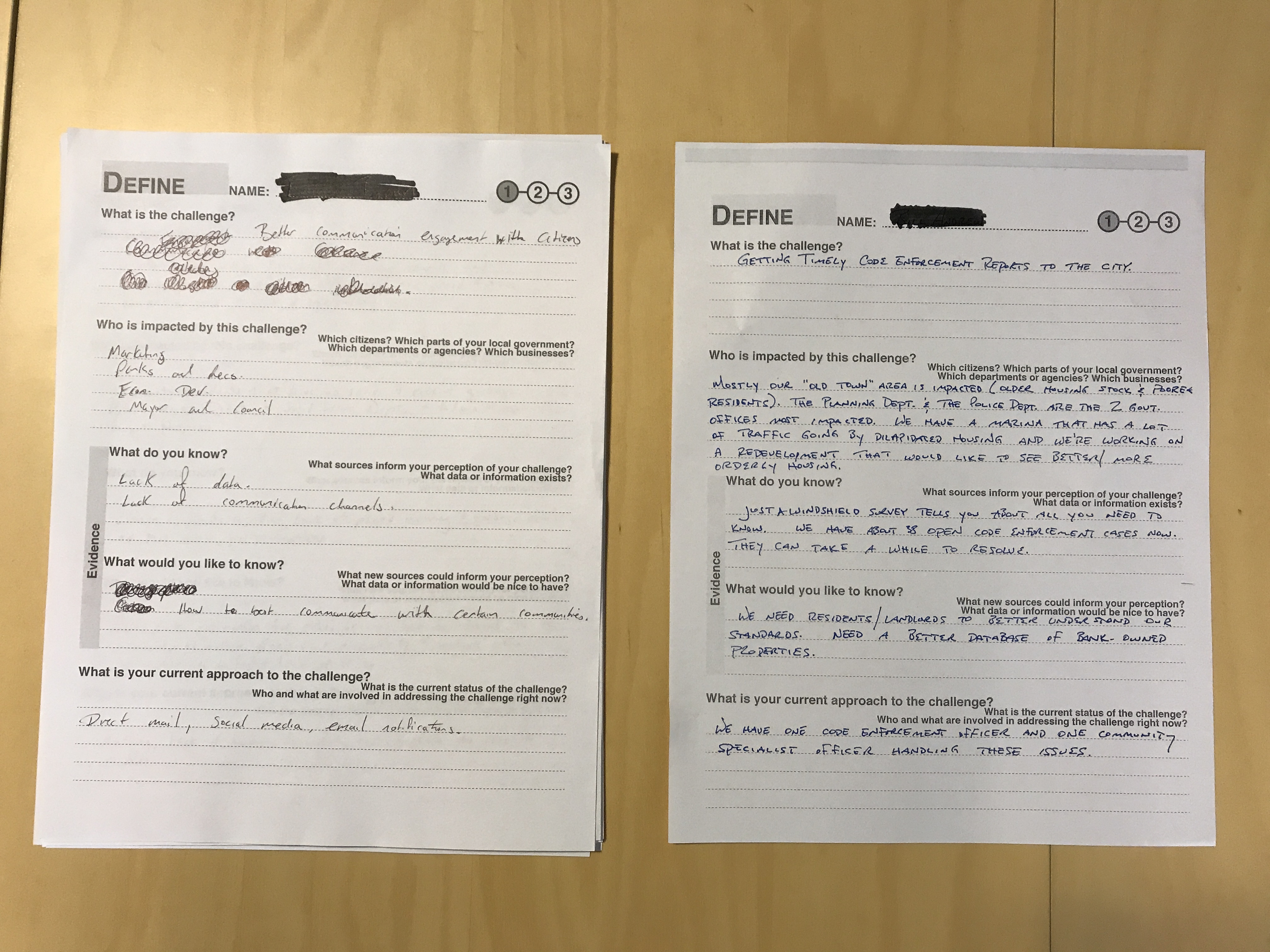

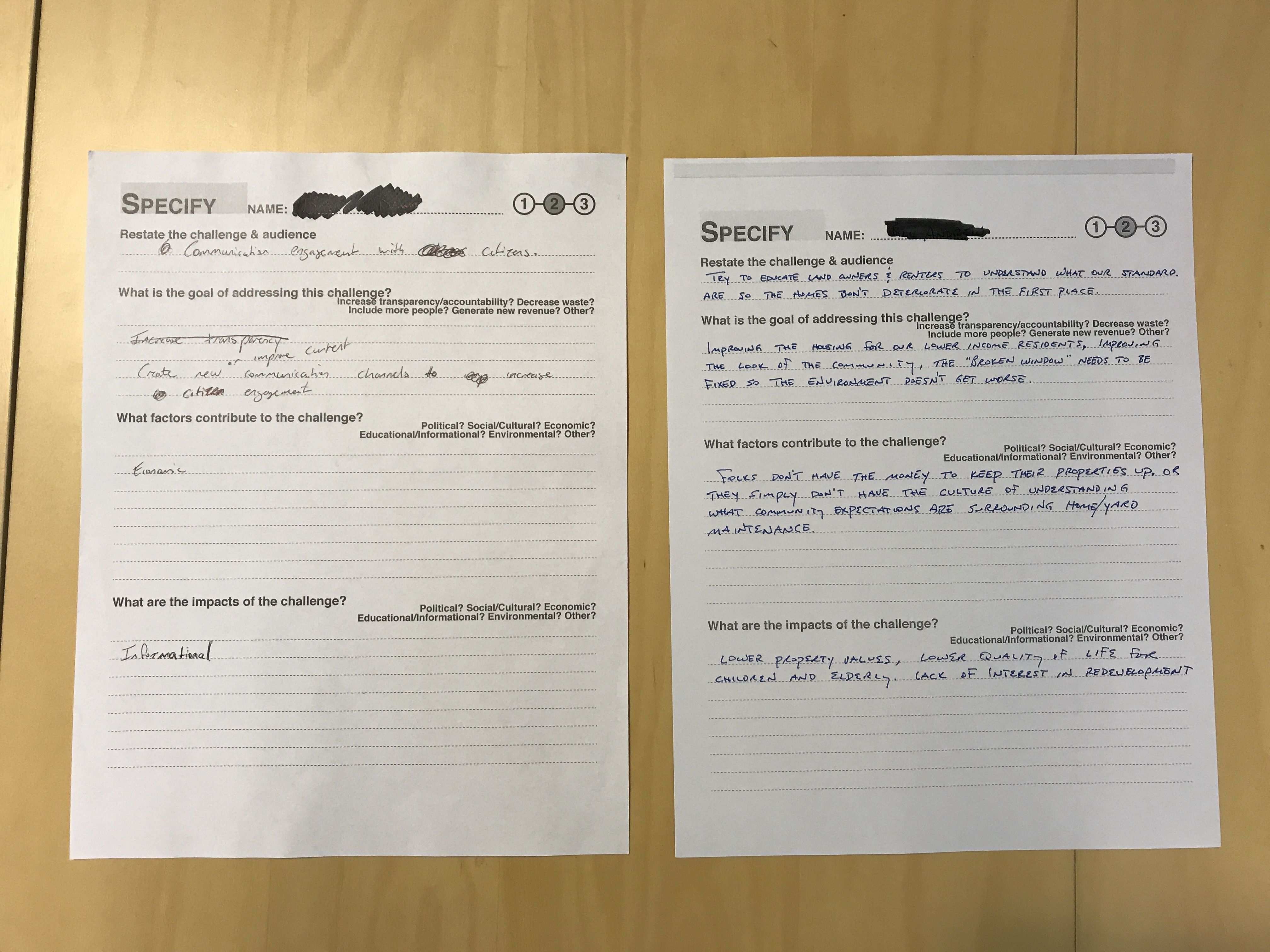

The structure of the activity focused on getting participants to incrementally define the nature of the challenges they were addressing. The Define worksheets asked participants to define a problem and its audience, as well as what is known, not known, and currently being done about the problem. The Specify worksheet asked participants to define the contributing factors and resulting impacts of the problem. The Propose worksheet asked participants to propose a strategy to address the issue. Framed within a day of discussing the smart community technologies, the assumption was that the proposals should fall within that domain.

Initially, we planned to distribute the Define + Specify + Propose worksheets in sequence, where individuals would first receive five (5) Define worksheets, then three (3) Specify worksheets, and one (1) Propose worksheet. After demoing the activity, we needed to reduce the number of worksheets—6 in total, with three (3) Define, two (2) Specify, and one (1) Propose—and distribute the worksheets as a packet. Distributing the worksheets as a packet allowed the facilitators to spend more time circulating, answering questions, and working with participants, rather than handing out materials.

Pass One (hi-res) showed that across all the worksheets, we needed to specify the time, which we eventually incorporated into a coversheet in a subsequent iteration. Additionally, the font was too small, leading us to redesign the layout to increase legibility. The Propose worksheet, in particular, needed a more explicit way of asking participants to specify the timeline of their projects.

Pass Two

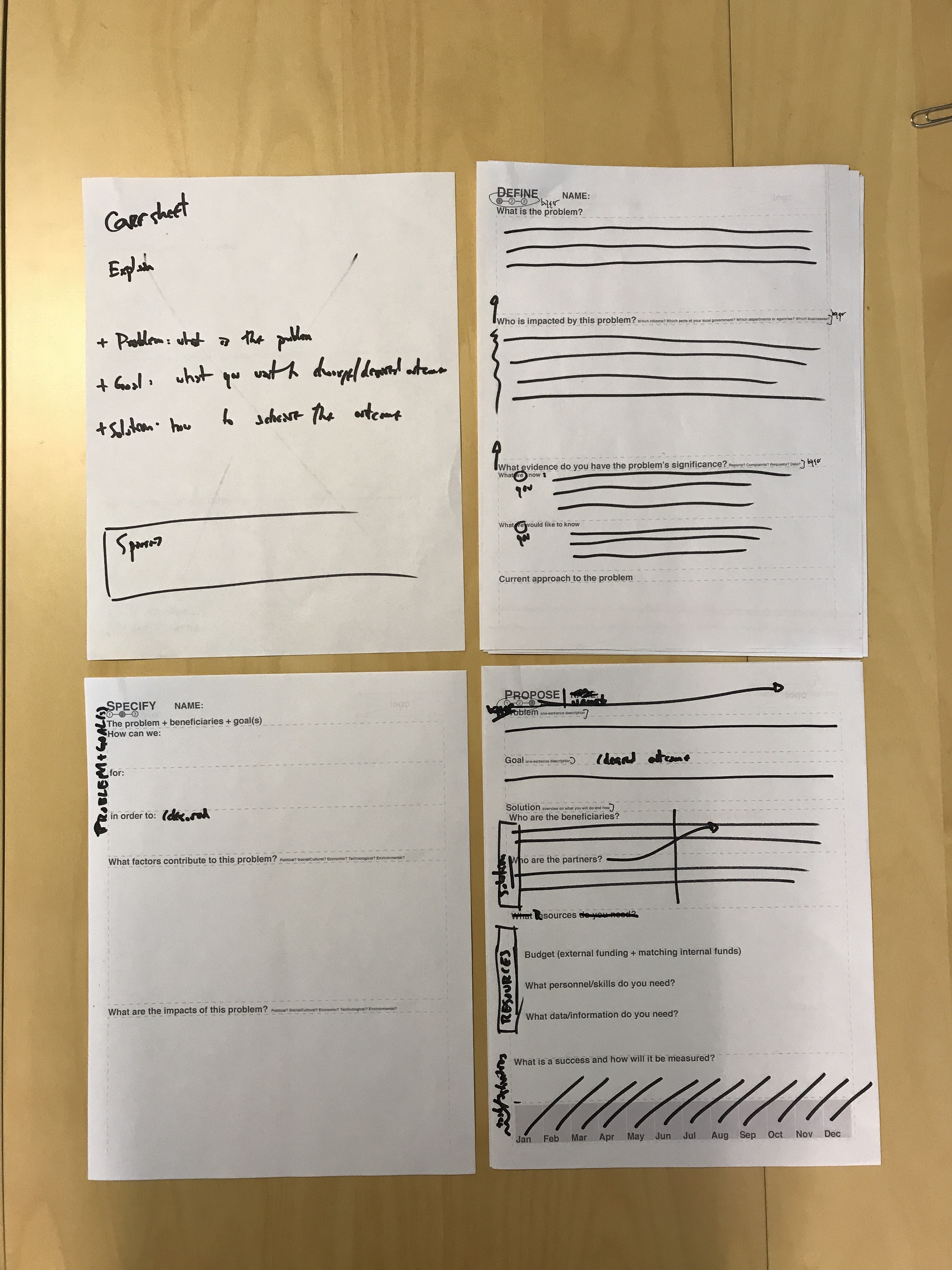

From feedback and walk-throughs, the second batch of worksheets featured a larger font. The increase in the font reduced the amount of space to write and made text crowded. We added a coversheet (seen here as a hand-written sketch) to give better directions to participants, and reduce the number of repeated explanations by the facilitators.

During this iteration (hi-res), we received feedback that the term “problem” was limiting (as in “What problem are you trying to solve?”). Additionally, after doing a dry run, we realized the unlined boxes led to difficulty for participants writing responses and for facilitators reading them.

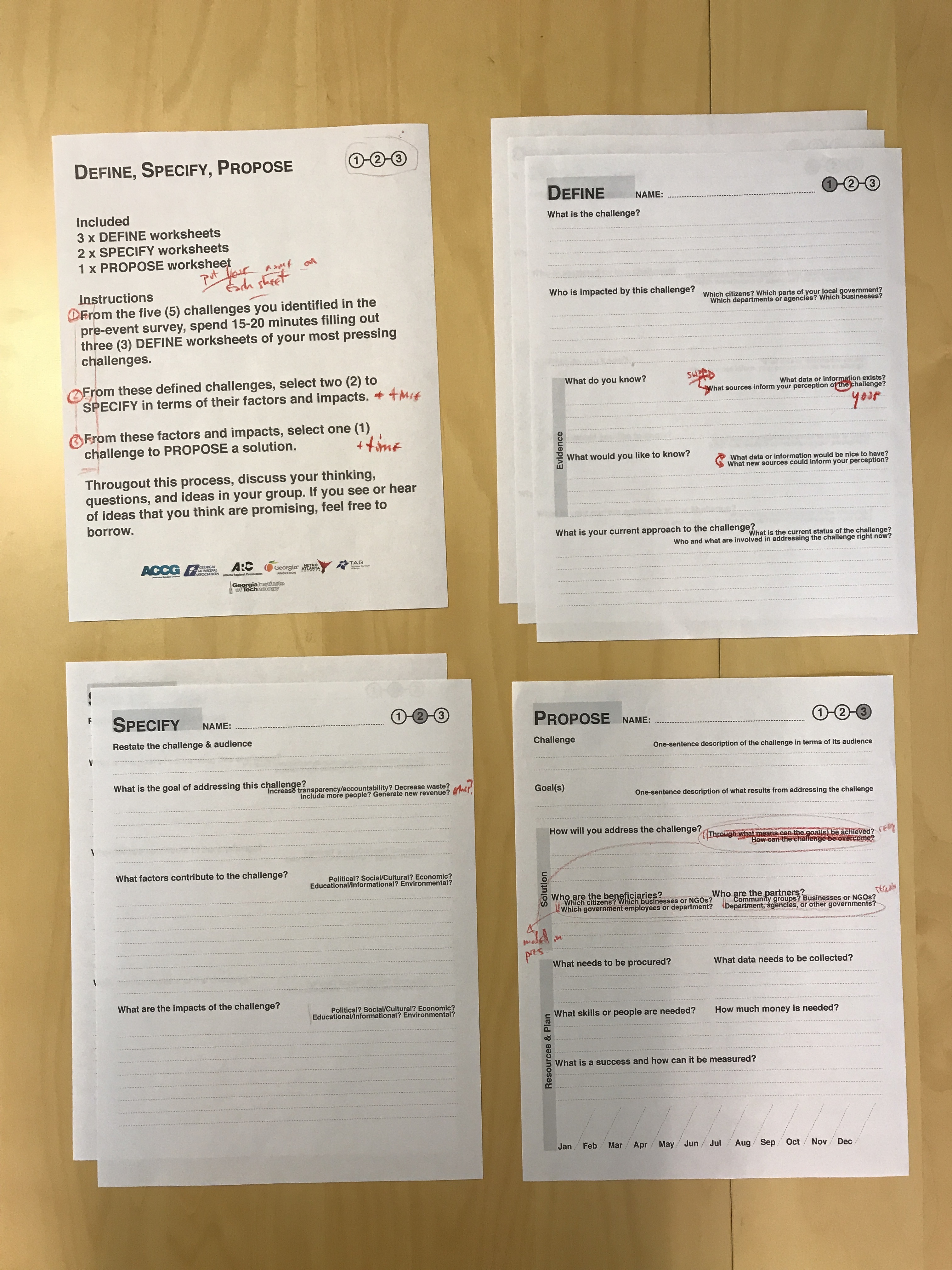

Pass Three

Pass Three (hi-res) featured another redesign of the layout, including adding lines to sections, more explicit delineation between sections of a worksheet (vertical labels), and a coversheet explaining the activity. The coversheet also solved an issue of where to place logos, which otherwise would have crowded individual worksheets.

In this iteration, we changed the wording from “problems” to “challenges” throughout the worksheets to encourage broader types of responses.

Final Iteration

In the final version of the worksheets (PDF), we added times to the coversheet and replicated the circled “1-2-3” from the upper right of the worksheets on the coversheet. On the worksheets, we removed extraneous text to give more space to write and reduce visual clutter.

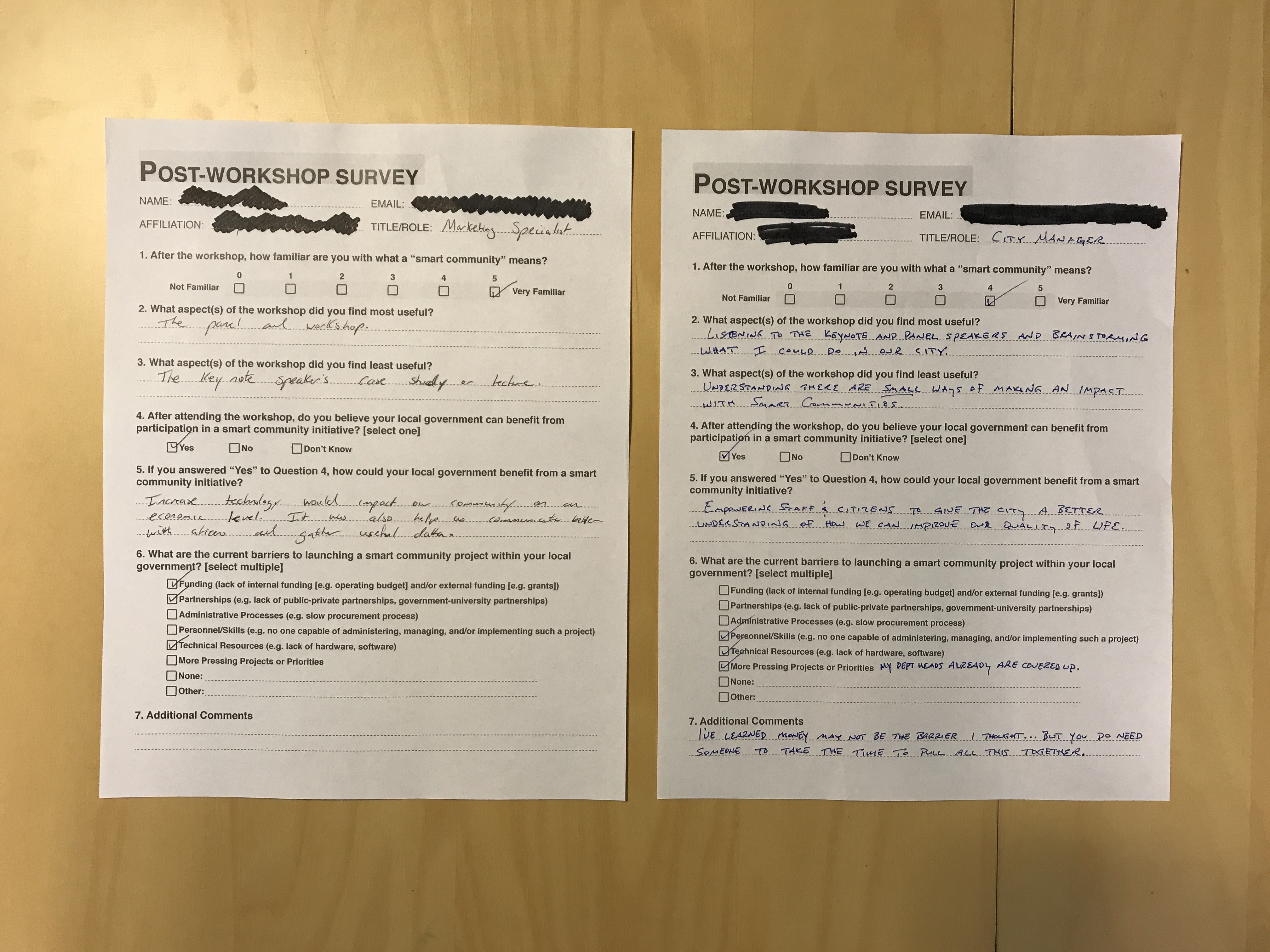

We added a post-workshop survey to the packets. We originally wanted to send the survey out to the participants in a follow-up email. After considering the response rate and wanting to capture an already captive audience, we translated the online survey into a paper survey.

Role of the Facilitators

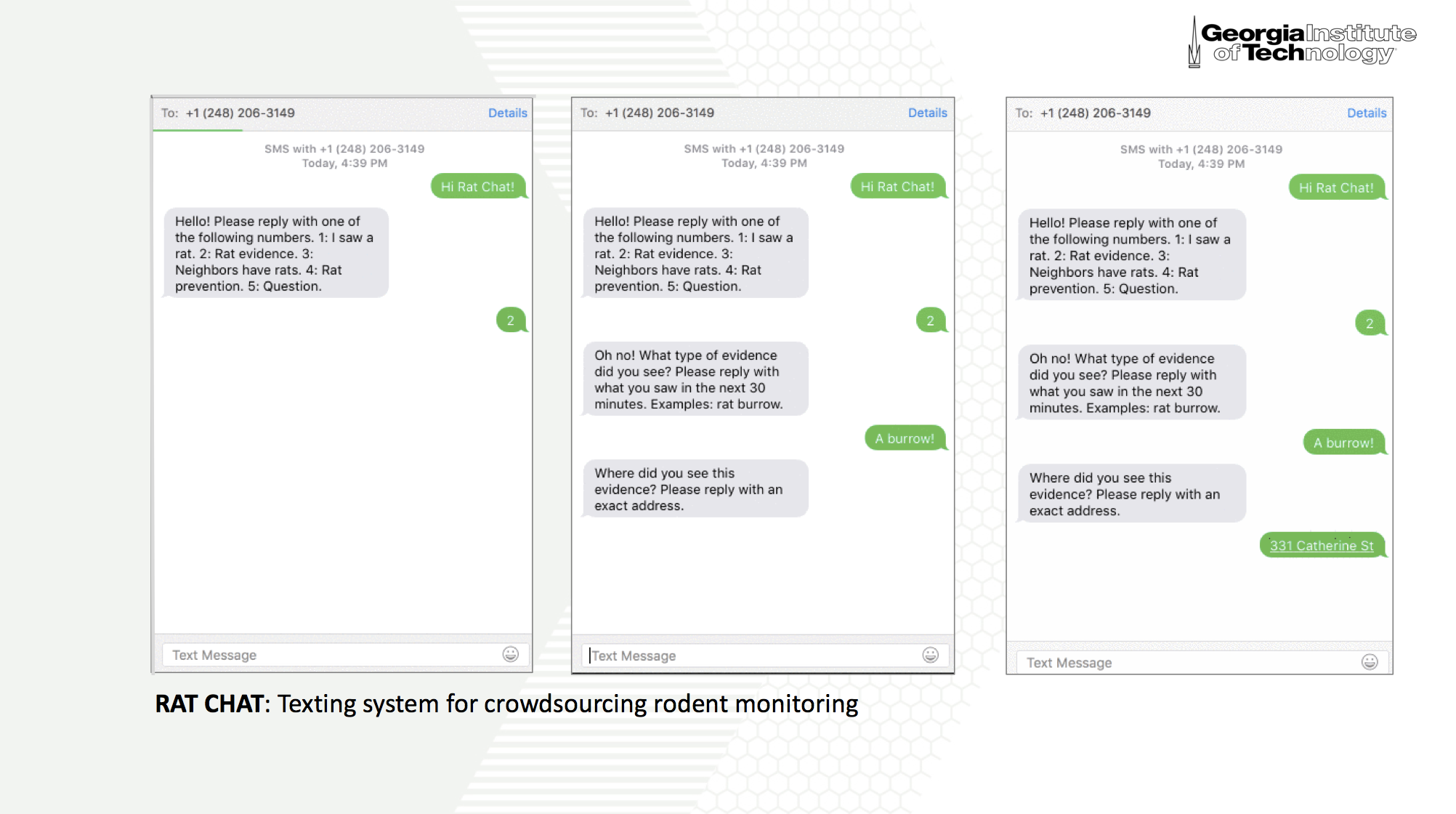

Rather than simply pass out the packets, we created a brief presentation that modeled the worksheets and showed exemplary first-step smart community projects.

Data Analysis

From the worksheets (hi-res define, specify, propose, and post-survey) and observations, we produced a few findings that are currently being incorporated into terms and conditions for the Georgia Smart Communities Challenge:

- A pilot program is needed: Participation in the event was overwhelmingly positive. Spread across 20% of the Georgia counties, participants located the inability to launch smart community pilots in a generalizable lack of dedicated resources (personnel, funding, partnerships, and technology) to these projects. A technical assistance program could help augment local capacity and supplement resources.

- Core issues: Challenges identified in the Define worksheets focused on three main issues: 1) digital services, such as a lack of platforms and services for data sharing amongst departments and with citizens, inefficient public communication channels, and other online government services (e.g. record requests); 2) mobility, such as first-/last-mile connectivity, traffic and congestion, and roadway monitoring (e.g. emergent conditions) and maintenance (e.g. infrastructure breakdown); 3) community-oriented development, such as promoting new investment while developing local skills/capacities and high-technology services accessible to all citizens.

- Data sharing: Many of the challenges (Define worksheet) and proposals (Propose worksheet) cited the lack of or need for cross-departmental and/or cross-jurisdictional data sharing agreements and infrastructures. Data sharing was a common precondition to moving forward on smart community pilots.

- Unknown skill needs/personnel requirements: Many of the worksheets featured blank sections. One of the most common was the personnel/skills section on the Propose worksheet. Based on observations and reflections from participants during share-back, this non-response can be interpreted as a gap in knowledge with regards to the technical capacities necessary to accomplish a pilot. This was further supported by the scant responses to the calendar. This absence indicates a lack of project management knowledge. As such, a technical assistance program needs to address these skills/personnel gaps.

- Funding is (always) an issue: Unsurprisingly, we found that many responses listed funding as the biggest barrier to launching a pilot program in their local jurisdiction. This finding confirmed our expectations.

- Ongoing education is necessary: Many responses indicated the need for ongoing educational resources to share and learn best practices. As such, Georgia Smart needs to include some educational programming that is both peer-to-peer and expert-led.

From these findings, we are currently developing the terms, conditions, and requirements.

–

-

The Georgia Smart Communities Workshop was held on July 21st 2017 and took place at the Atlanta Regional Commission (ARC) offices. The event was organized by Georgia Institute of Technology in partnership with ARC, Association County Commissioners of Georgia (ACCG), Georgia Municipal Association (GMA), Georgia Centers for Innovation, Metro Atlanta Chamber, and Technology Association of Georgia (TAG). The workshop convened local governments, government associations, and industry and academic leaders to discuss the application of various computational and digital technologies (e.g. Internet of Things (IoT) devices, intelligent infrastructures, data centers, public wireless, information and communications technologies (ICTs), and more) for local government. These types of technology projects and initiatives often fall under the label of smart cities—a label that presumes that individual municipal governments are the primary governmental actors in such efforts. Although this presumption tends to be true, its truth depends on a host of external factors that bolster the prominent role of cities (and often large cities) in such efforts—an increased focus on metropolitan areas as sites of innovation; the ability for municipal governments to participate in various technical assistance programs and policy networks; the repeated meme that global population is becoming and will increasing become concentrated in cities. The Georgia Smart Communities Workshop, on the other hand, fostered discussion about these sorts of projects and technologies at different local government scales. In Georgia, the presumed smart city is Atlanta. As such, the workshop brought together cities, counties, and conglomerated city-county governments from across the state to discuss the application of technologies and policy initiatives we call smart communities. ↩

-

The workshop drew more than 70 participants, including personnel from 20 city governments, eight county governments, eight community improvement districts, and eight US congressional districts. These participants were spread across about a fifth of Georgia counties. ↩

-

The program, called Georgia Smart Communities Challenge, or Georgia Smart, is still being developed in full as of early September 2017. The announcement of Georgia Smart is planned for Fall 2017. ↩